Why do we create whole buildings dedicated to people who died? Why do we recite speeches of people who lived hundreds of years ago? And how do we determine who deserves it? All societies have a way of remembering the dead. From the stone cairns of Highland Scotland to the pyramids of the Ancient Egyptians, we respect those who came before us.

And yet, we don’t remember everyone. In fact, we can be very good at erasing the histories of people we perceive as beneath us or threats to our own lives. At the moment, this tendency is coming back to haunt us. We can no longer lift up the lives of some without a long, hard look at their legacy. After all, some of those memorialized in statue would be condemned as murderers in the present day.

The trouble is that once laid to rest, the past does not tend to remain in peace. People must reckon with their choices, particularly those in a position of privilege. It is a painful experience for everyone, but a necessary one. The result may be a better world in which everyone is valued and remembered.

Memorials Worth Remembering?

When people think about their history, who do they remember? White people can often track their genealogy back for hundreds of years. For marginalized groups in the United States, particularly Black and Indigenous people, it’s much more difficult. Their lines and traditions were abruptly cut short and shifted in the service of white imperialism. It’s no surprise that they see the memorials to the white men who carried out that violence as violent reminders.

But as those statues topple, one by one across the world, it’s bringing to light new criticism as municipalities debate how to replace them. “All your faves are problematic” is more than just a popular saying on Twitter. This discussion about which memorials to create and which ones to keep is only a small part of the broader topic about who we choose to remember, and how we remember them.

Monuments to White Supremacy

In the past few months, statues of Confederate officers and early proponents of European imperialism and slave trade like Christopher Columbus have been pulled down in protests across the world. More recently, protesters turn a critical eye to more permanent structures. A protest at Mount Rushmore highlighted the debate. The carving, which dates to the 1940s, was constructed on a mountain known by Lakota Sioux people as “Six Grandfathers.” This monument to presidents, some of whom had been slave owners or held clearly racist views, was meant to increase tourism in the area. Now, even some descendants of the sculptor demand its removal.

“Heritage Not Hate”

There cannot be struggle without a backlash. There are plenty of people who would like to see these monuments and memorials remain in place. Their argument is that these icons are representations of “heritage, not hate.” Without a critical lens, people may seem like they are simply upholding their racist ancestors. Protesters argue that keeping a statue of a Confederate or slave-trader in a place of prominence isn’t telling the full story.

These changes are putting people’s beliefs to the test. In late June, the government of Mississippi voted to remove the Confederate emblem from their state flag. As the last state to eliminate such references from their state, this was a notable change. It had the support of the vast majority of the state’s legislative branch. But it is still a contested change. People who are used to determining whose history gets remembered are learning that wiping away others’ stories is an issue worth fighting for.

Dememorializing and White Supremacy

Recent analysis on the subject of civic memorials brings up important questions. What do we decide to memorialize? And what do we throw away as unnecessary? People tend to think about statues and buildings as the most obvious monuments to white supremacy. But it bleeds into society in other ways. Destroying the history of marginalized groups is a practice that is thousands of years old. It’s also common in the present day.

For the past few years in North Dakota, residents of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation have fought the building and use of an oil pipeline that crosses the reservation. Their argument is that the land belongs to them. And as controllers of the land, they claim the right to prevent developments that may pollute their access to water. This dispute gained worldwide attention in 2017, and continues in the present day. But the claiming of tribal land and the destruction of historic sites and memorials is not just a problem for Indigenous people in the United States. It’s something that Indigenous people in Canada must combat on a regular basis, as well.

Gentrification is another common example, and all too easy to find nearly anywhere in the country. Historic neighborhoods and communities are shunned by white people, who think that it isn’t classy enough to live there. This keeps prices down. Eventually, someone gets a burning ambition for urban renewal. They start buying up the properties and knocking down the old buildings. They change the tenor of the community by centering it on the things white people want. While people usually consider this in the lens of housing, it’s often used on community gathering places, as well. Old schools, churches, shops and community centers that primarily served marginalized groups are destroyed. In their places come the gyms, parking lots, urban entertainment venues and trendy housing that white people like. And as these buildings go down, the cultural memory of these people is often swept away.

Cultural Memorials

In various cultures throughout the world, memorializing the dead is a vital part of remembering them. Specific rituals guide the living in offering a moment of thought for loved ones or important people who have gone before. Although there are hundreds of examples throughout history, it’s worth keeping in mind that they can be permanent or temporary.

Ofrenda

Like the English, the Spanish colonizers brought white rule and religion to the Indigenous people of North, Central and South America. The forceful imposition of Catholicism on the people of Mexico blended ancient traditions into a holiday known as Día de Muertos. It’s called the Day of the Dead in English. This tradition features an altar on which people can place pictures and reminders of their loved ones who have died. It is a memorial that families create each year on November 2nd, a day when many people believe their loved ones can come visit them.

Scottish Cairns

Everyone knows a famous Englishman. What about a Scot? Before the English fought a war with America, it nearly decimated the Scottish culture. In many ways, much of what is left remains because it is permanent. Cairns are a good example. This is a tradition that dates back thousands of years. Instead of an elaborately-carved headstone, people would place a stone in a pile. It was an important ritual to take a stone from a valley and put it on the cairn of a loved one. This served as an important reminder of local memorials. It also made them semi-permanent. For example, the Clava Cairns in the Scottish highlands are about 4,000 years old.

Spontaneous Memorials

A cross on a highway. A small pile of stuffed animals on a busy street. In the absence of a permanent memorial or a way to say goodbye, people will remember any way they can. Spontaneous memorials are such a common feature of the American experience that we might not even see them as a real memorial. After all, once the posters get rained on, what happens to them? When the teddy bears have sat on the street for weeks, what then?

This is the work of archives. For centuries, the experiences of people who weren’t famous enough to have their works placed in a formal memorial relied on their families. Much of what we know about marginalized groups’ histories depends on their ability to hang onto these important records. If their families would not or could not save them, then they might be destroyed entirely.

For decades, archivists have dedicated their time and storage space to the collection of public memory. This is where a lot of the pictures or mementos that might have been destroyed end up. But the ability to display them is a matter of resources. We have all the money in the world to celebrate every aspect of an American president. Yet, everyday people might be all but forgotten outside of their families. Interest in documenting the lives of marginalized people has led to funding that can bring these stories and pictures out of the darkness and into the public mind.

Live Memorials

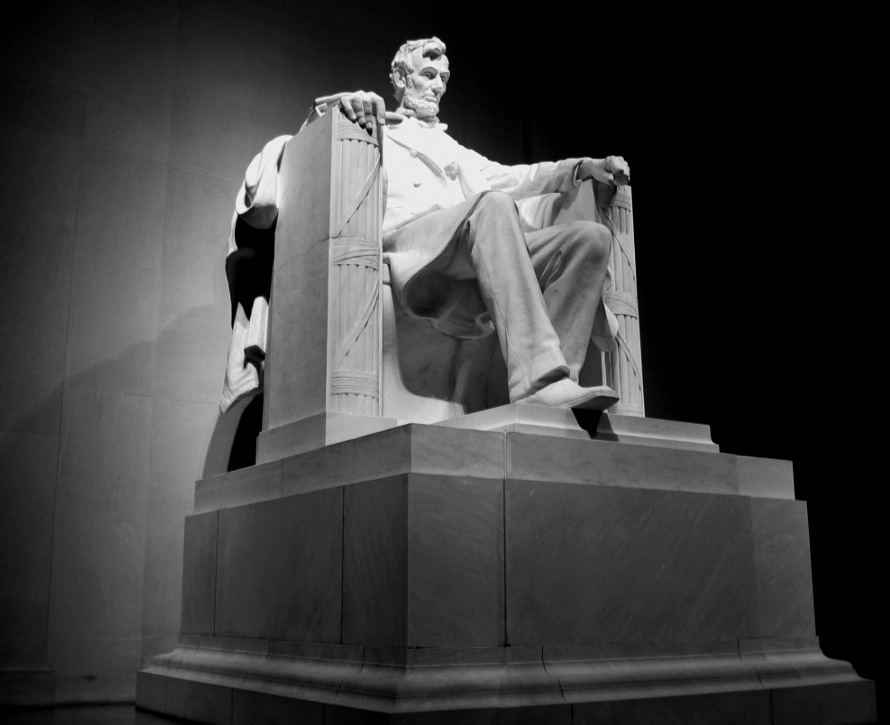

When we think of a memorial, it’s easy to confuse it with a monument. After all, Lincoln and Jefferson have massive memorials built of stone that millions of people visit every year. In fact, there are many different kinds of live or living memorials that people carry out to celebrate their loved ones. It may include a disposition of their final remains. It may be a reminder of their words or important deeds years after they died. These memorials may not be easy to visit, but they keep a person’s memory available to the living.

Oral Traditions

Before the advent of typing machines or recording equipment that could document a person’s words in real time, people relied on oral traditions. Remembering what someone said is an important way to memorialize them. Famous people have books, paintings and statues or buildings to memorialize them. For others, their words are all that is left. It is in this spirit that many Black people recite the words of their ancestors. One of the most popular is Frederick Douglass’s speech “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” This speech, given in 1852, outlined how this day of American freedom was definitely exclusive to white people.

Of course, it isn’t impossible to misuse a memorial. Many white people like to quote the speeches and writings of Martin Luther King, Jr. to criticize outspoken Black people. This creates an interesting discussion about how the famous civil rights advocate’s words are used to achieve a specific end. Some people say that King was always in favor of finding a compromise. Others say that he had to win over a racist white audience, and he was still shot for advocating nonviolent protest.

George Floyd

The death of George Floyd brings a stark contrast to the way that people are remembered, and why. When a police officer killed George Floyd on Memorial Day, despite many bystanders’ calls for him to stop, he ignited a fire that burned worldwide. Floyd’s memorial had thousands of attendees, who saw the casket bearing his body for a final rest. Today, dozens of tributes highlight the man.

Some people argue that Floyd wasn’t a good person worthy of such remembrance. Protesters and advocates for Black Lives Matter say that Floyd’s character did not earn him a death sentence. They rail against the revisions that white people make when a white person kills a Black person. They point to attempts to criminalize Black people as a justification for their deaths, as people did after the Black children Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice were shot after committing no crimes. They argue that if white people fight for the memorials of colonizers and slave-traders, they aren’t the best judges of who deserves to be remembered.

“Rest in Power”

When a loved one dies, we often want them to rest in peace. But another phrase is taking over. Used to memorialize people whose lives were cut brutally short, “Rest in Power” has a unique meaning. It’s not a very old phrase, only about 20 years. Its etymology seems to start in Northern California, after well-known graffiti artist Mike “Dream” Francisco was murdered during an armed robbery.

The memorial phrase became associated with the Black Lives Matter movement after the death of teenager Michael Brown in Missouri. His death at the hands of a white police officer ignited a movement against police brutality nationwide. Today, people who want to remember Black people, people of color or other marginalized people killed by white people may use the phrase. They see it as a reminder that the person does not disappear from public memory when they die.

Ways to Memorialize

Memorializing a loved one comes in a variety of ways. In the early days of grief, many people act like a living memorial for the person who died. Over time, they may choose to participate in events or create permanent, lasting reminders of the person for the people who are left behind. These popular memorials can help people connect with their loved ones, even those who died long ago.

Memorial Services

Memorial services commonly happen shortly after a person has died. They are similar to funeral ceremonies, but they do not necessarily need to coincide with the disposition of a person’s last remains. As such, memorials can happen almost anywhere and feature almost anything. Many families like to incorporate the disposition of ashes as part of a memorial service, through scattering, burying or placement in a cemetery’s columbarium. It’s an event where loved ones can gather to share memories and grieve together. This means that the memorial may or may not be permanent, depending on what the family feels is most appropriate.

Visual Tributes

Since most people aren’t well-known enough to have statues or buildings named in their honor, visual tributes tend to be smaller. Outside of the family property, people may choose to create a lasting memorial for a loved one in a place that was particularly meaningful. For example, family members of a patron of the arts might choose to have a tile in a popular performance space dedicated to their loved one. Someone who loved the outdoors might have loved ones who dedicate part of a trail or a cleanup program after them. These tributes sometimes require an investment of time to keep up the memorial. In most cases, it just calls for a donation of a specific amount of money to a good cause.

Annual Events

Although a memorial service is typically part of the experience for the recently bereaved, there are plenty of ways to memorialize loved ones on a regular basis. Family members who were pleased to host an annual get-together like Thanksgiving or a summer barbecue might be best remembered with a memorial event on these days. Gathering together to share memories and the loved one’s favorite meal are great ways to keep their stories alive for future generations.

Home Memorials

Ultimately, many people choose to keep a memorial at home to remember a loved one. Since most people are cremated now after they die, their remains can be kept in any spot of honor. The variety of cremation urns gives endless opportunity for family members to build a memorial that their loved ones would have appreciated. This might include a collection of pictures, or even a 3-D printed urn of the person or their favorite hobby.

History is too often written by the winners. Those who lost may be erased completely. Even in a world where the written and visual record is massive, it takes work to provide a sufficient memorial for those who died. Even now, the people with the most privilege are the ones whose legacies remain.

Instead, people call for a new definition of a memorial. They want to remember those who died without dominating others. They want to memorialize people who inspired everyone left behind to do better. They call for others to preserve the memories of the oppressed, as well as those in power. By listening to this call and re-examining how we decide who to remember, we work toward a world where everyone is remembered.